Entry #1: The Way of the Mindless Herd

How the American public has lost the ability to think for itself, and what is to be done about it.

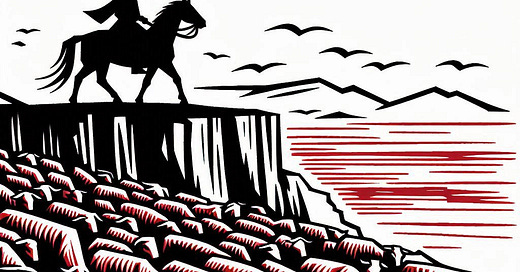

I have been greatly distressed of late with the knowledge that the mass of men and women in today’s society have lost the ability to think for themselves. Over the course of my lifetime, but especially over the past twenty years or so, the American populace—which, being an American myself, is the only populace I can fairly claim to be familiar with—has devolved into a herd of dumb, driven cattle being led to slaughter by unscrupulous men who care only for the profit to be made by selling their followers as cuts of meat on the grocer’s shelf.

As sad as it is for me to say, the average Joe or Sally I speak with today is no better able to construct a well-supported argument in the area of, say, civics and political discourse than a cud-chewing cow in a farmer’s field. Gone are the salons where men discussed great books and ideas. Gone are the political debates where legislators versed in classical rhetoric and logic engaged in intelligent discussions on pressing issues of the day. They are vestiges of a distant past, replaced by online forums where faceless people insult and snipe at one another like unruly children.

Now, before you begin casting stones at a well-meaning old curmudgeon with aching joints and brittle bones, let me say that the fault for this sad state of affairs does not entirely lie at the feet of the general public. It has become exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to hold within our overstimulated minds even a single original thought in a world that is intent upon stripping us of our very capacity to do so. Every waking minute of every day, we are being bombarded by flashing ads, dancing videos, and clever memes, all aimed at selling us something, whether that be a product or a political cause.

No wonder we fall prey to snake-oil salesmen seeking to fill our minds with crockpot theories that have no more basis in fact than the tooth fairy. Indeed, I would argue that we are more awash in superstitions today than we were half a millennium ago before we were led out of the Dark Ages by the Scientific Revolution. After 300,000 years of climbing to the top of the food chain, mankind has willy-nilly thrown off our inheritance in favor of the unthinking, tribalistic impulses of our distant lizard brains.

I myself am hardly immune to the pernicious influences of our media-saturated society. Many a morning have I allowed my precious peace to be disturbed by fits of outrage brought on by a mean-spirited post or tweet that traverses the digital desert of my newsfeed—this despite the fact that I have neither met the originator of the offending post/tweet, nor had the opportunity to question his motives or inquire into the facts, if any, that support his position. For all I know, he is not a man at all, but a bot housed on a computer in someone’s basement in Russia.

It is madness. Among the many pieces of commonsense wisdom that I took from my late father, a man who instilled in his six children the vital importance of never conforming to the ways of the herd, was that no sane person would ever allow himself to be swayed by the words of someone he has not had the opportunity to shake hands with, since a handshake tells as much about the person as the words that come out of his mouth. In short, one must always consider the source before allowing a new piece of information into one’s head, much as one should know who provided the food one eats.

It was for this reason that my father grew his own food and hunted his own game, teaching his sons to do so as well. For him, self-reliance and acuity of mind were two sides of the same rare and precious coin, one that you earned with great industry and held tightly in your hand lest someone try to steal it. He was, after all, a Scot by blood, and we all know that Scots are as prudent as they are cheap.

Alas, my father, were he alive today, would no doubt be disappointed to know that his middle son James made his living in the dubious field of public relations, which, if Dante had a circle for it in Hell, would be found somewhere between Fraud and Treachery. I am, or was, a spin doctor by trade. After a short stint as a newspaperman, I went into the corporate world where for thirty-plus years I plied my living as a spokesperson for multi-billion-dollar companies. I sold my Scottish soul for the golden handcuffs of a six-figure salary and a boatload of incentive stock options, employing my talents, such as they are, in the service of dressing up the deeds of soulless corporate leviathans whose interests were all about boosting the bottom line.

My only excuse for such ignoble behavior is that I wanted to provide my family a lifestyle with greater material riches than those that I knew when I was growing up in our cramped, one bathroom farmhouse with its drafty windows and uninsulated pipes that froze during the winter. We grew our own vegetables in the garden out back and shot the game that our overworked mother set before us on the dinner table. Our horse barn was forever leaking and in need of fresh tarpaper. Our farm equipment, bought second-hand because that was all we could afford, was always breaking down just when we needed it. Is it not the American dream to want to do better than your parents?

I know now that what we had back then was the definition of true riches. For though we shoveled manure and pulled weeds under the hot sun and picked pellets from chunks of squirrel and pheasant in steaming pots of vinegary hasenpfeffer, at least then we knew what was real and what was not. We could walk down real streets talking to real people, breathing real air, delivering real newspapers to real neighbors who paid with real coins. (Yes, I was a paper boy, a profession that, like so many others, has gone the way of the Dodo bird.)

As for diversions in those days of only five channels on TV, we played baseball in the yard, and fished for bluegills in the creek, and read books, loads of them, borrowed from the library or the Bookmobile. We fed our imaginations not from the Digital Pixieland of massively multiplayer online games, but from the stuff of nature, which in turn fed our ability to spot a huckster from a mile away.

Did we get fooled?

Of course.

Did we have our prejudices? Our delusions? Our superstitions?

Yes, yes, yes. But those were dispelled through higher education, which our parents insisted upon. That’s right. We believed in education back then. In science as well. In the importance of opening our minds to other perspectives and in grounding our opinions—always, always, always—with the hard stuff of facts and evidence.

Faith too. Every Sunday morning our mother dressed us up and took us to church to stand before the cross and recite the words that the nuns drilled into us from our catechism books. But even our faith was grounded in the real world, for while my mother was Catholic, my father was not a believer. His religion was nature, which taught complementary lessons about the renewing power of the seasons and the importance of tossing seeds in fertile ground.

And from this compost of self-reliance and industriousness, tempered by education and a spirituality grounded in nature, grew the ability to distinguish between true knowledge and the collective thinking of an institution or party, which, after all, isn’t thinking at all but propaganda. Call me old-fashioned, call me a fool, and you would be partly right in saying so. For though I am old, I am not fashionable in either my clothes or my views. And if I am a fool, at least I am an honest fool. I aim to sell you nothing. My wisdom, such as it is, comes as free as the air we breathe.

And so, here is my story, for whoever cares to listen. It is the story of a sojourner in a world that has been lost but not forgotten. A world of real things and the commonsense lessons they taught. Of sun-warmed tomatoes yanked fresh from the vine, of fireflies that flashed in the night, of strings of green slime that stuck to your feet when you walked through the creek.

It was real, it was magical, and I am richer and wiser for having known it. I can fend for myself. I can think for myself. I follow no herd, aware of the tricks of the men who drive them. Is that not, in the end, the definition of freedom?

I love this piece! It rings true in so many ways. A bit pessimistic, perhaps, but it would be odd NOT to allow that mood to begin to sink its roots into you, if you spend even 15 minutes per day watching cable news (no matter the channel or its bias - and every channel seems to have one.)

My father was also the ultimate non-conformist and was definitely not fashionable!! What he WAS was cheap, and I say that affectionately. My parents had 9 kids (I was the 8th of 8 boys, before they were finally blessed with a daughter), so some of the frugality was logical. But, he took it to a new level (can't one purchase clothes that don't clash at the Salvation Army or garage sales?).

By luck or design my parents sent me to a Jesuit high school where I grew up in Detroit, and their central theme was: question EVERYTHING! Combined with my own personality (analytical to a fault), this was a wonderful influence on my formative years.

Very happy I found this substack (I got an email about it for the first time this morning as A Peaceful Man follower, which I found by way of Humble Dollar. So, it turns out the internet can be a tool for good, as well as folly! Looking forward to future curmudgeonly installments!!

Fantastic piece. So well said and written